Carell Technologes - my startup

20 Oct 2019 - Jeremy See

20 Oct 2019 - Jeremy See

Carell Technologies: My wearables startup

Before starting my undergraduate degree, I co-founded a wearables startup. My team and I spent months developing a fever-detection smartwatch for children, the Carell Smart Band.

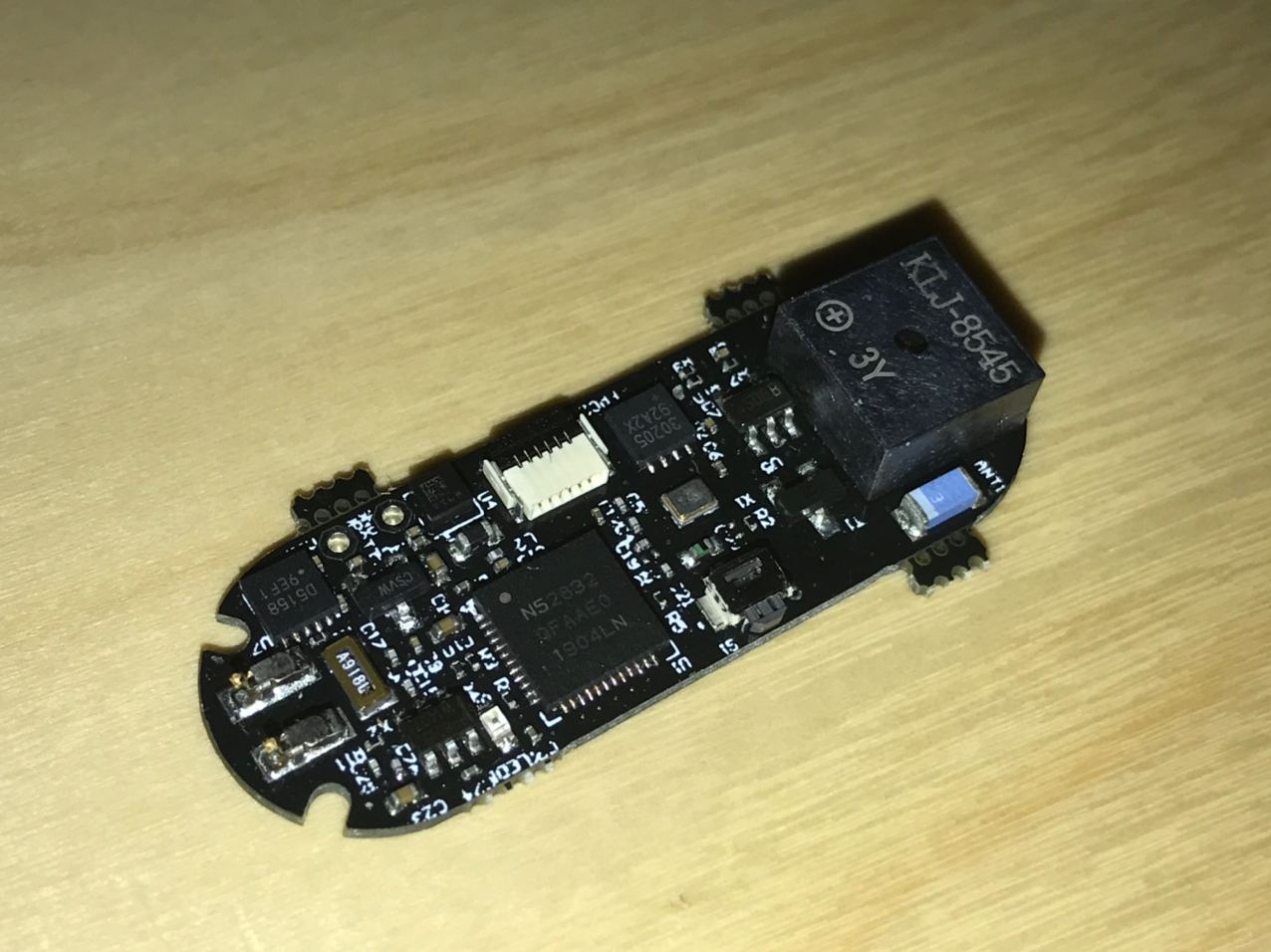

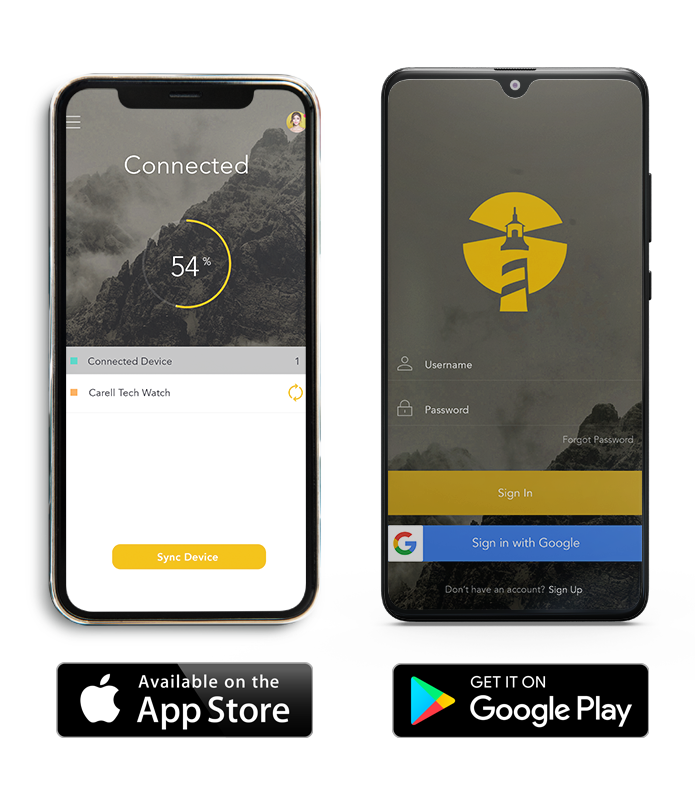

Carell Smart Band was a device meant to monitor the temperature of a child and detect when an abnormal spike (representing fever) may occur. This allows parents to go to sleep with peace of mind, knowing that they would be alerted if anything went awry. The product was launched on Indiegogo in September 2019. My contribution was the electronics, firmware, and mobile application for the product.

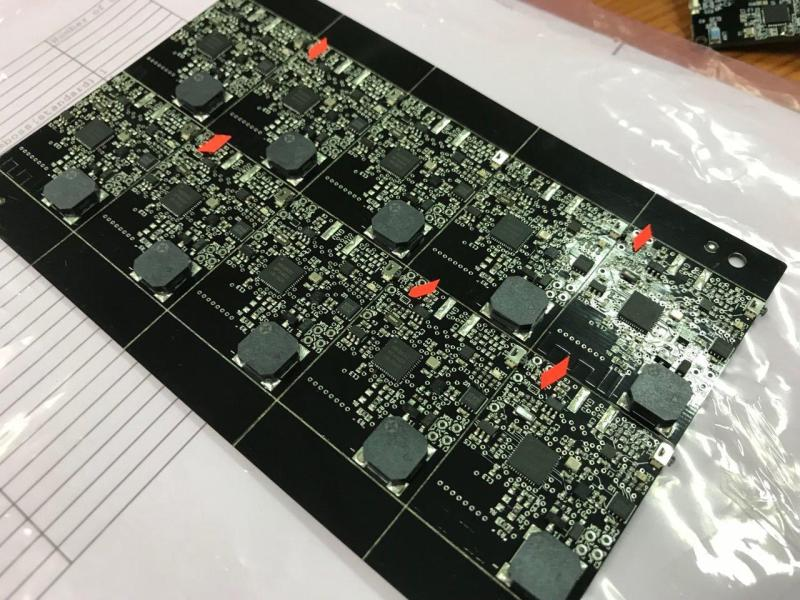

Electronics Design

For the PCB, I used EAGLE to design several iterations of the high-density PCB to fit within the wearable band. The process required an intimate knowledge of the SMT process in order to ensure a high yield during manufacturing and keep costs low. Smaller components were required for the production-ready version, with a more careful layout to fit in the mechanical housing.

The main challenge I faced was the difficulty in finding appropriate parts to minimise the footprint of the design. As the wearable featured an LCD screen on the top, components could only be mounted on the bottom side of the PCB, making a high-density layout difficult. It took a long time to fine-tune the final design. With CAD and some smaller components (0201 passives and QFN packages), the final design was done and ready for manfuacture.

Firmware Design

For the firmware, I used Nordic’s SDK in SEGGER Embedded Studio and their Softdevice Bluetooth Stack to create a low-power BLE application to take in sensor data, process it and determine whether it was an abnormal temperature out of the historical bounds, and alert the user via a smartphone application with a custom BLE Service. This required an intimate knowledge of C and low-level architecture, as the lack of an OS for scheduling effectively meant that this was bare-metal programming based on interrups. I optimised the code for stability and ultra-low power consumption around 1mA on average with the sensor always active. I had to heavily utilise the deep sleep mode of the nRF52 chip to minimise CPU usage as that was the biggest power sink.

Debugging was a pain due to the asynchronous nature of the interrupt-based architecture. Bugs were easy enough to point out, but finding out the cause of high power consumption was a tedious, iterative process of isolating certain components and testing their effect on the system as a whole, one by one.

Based on some back-of-the-envelope calculations, I estimated the battery life of the device to be around 2 weeks. However, with field testing, it was closer to 1 week due to self-drain of the battery over time.

Android Application

For the Android application, I used Android Studio in Java to create a basic application to pair with the BLE device, save its UUID for future reference, receive data through a custom BLE service, and upload data at intervals to a Google Firebase backend. This app was for the initial trial run with volunteers, to gather data to train our algorithm to detect abnormal temperatures at the wrist and correlate them to events like a fever.

As it was my first app, I faced a lot of difficulties managing the different activities in the app as it was a different style of programming from what I had been used to. However, I eventually managed to understand it and create a basic app that was ready for beta testing with the trial run. We were planning to create an iOS version after the launch, unfortunately that never materialised.

Conclusion

This entrepreneurial journey has been eye-opening, to say the least. Heading a small technical team to develop hardware and software in parallel all under a bootstrapped budget was no mean feat. While we didn’t manage to bring the product to market, I’m certain that the lessons learned here will be invaluable to future adventures!